For our assignment, we were given a few terms collected from the book Universal Principles of Design. I was given the following phrases to explain and analyze:

- Fibonacci Sequence

- Golden Ratio

- Most Average Facial Appearance Effect

- Normal Distribution

Most people are familiar with Normal Distribution as the “bell curve” when plotting values across across of a distribution. In the book, this example shows average height among men and women. We might have come across the terms in standardized testing or being graded in a class. It is a statistical approach of measuring variance from the average. In a normal population, approximately 68 percent of the population falls within one standard deviation of the average, a plus or minus of 34.13% away from 50%. These percent values, or percentiles, help judge the distance from the “normal” or “average” value. If 50% is average height for a man, then someone who is 99% is much taller than average, and 1% much shorter.

The Most Average Facial Appearance Effect (or MAFA Effect, here I will call MAFAE) builds off of this understanding of calculating what is average. The MAFAE asserts that, “people find faces that approximate their population average more attractive than faces that deviate from their population average.” In relation to MAFAE, “population refers to the group in which a person lives or was raised,” and “average refers to the arithmetic mean of the form, size and position of the facial features.” When we think of a perfectly Normal Distribution, when all values are averaged you wind up in the middle with whatever value is at the 50th percentile. In a similar approach, a visual description of the MAFAE blends all faces together to depict the most “average” face, which is also described as most attractive.

With this kind of visual averaging, the resulting faces are usually more symmetrical, which has found to be a valued when judging attractiveness. Further, the MAFAE is used to explain why people may find members of the same race attractive. This is justified by what is speculated to be a genetic, evolutionary preference, and perhaps some innate fear or distaste for the unfamiliar. According to MAFAE, unfamiliar groups can eventually become familiar, and henceforth the “cognitive prototypes are updated and the definition of facial beauty changes.”

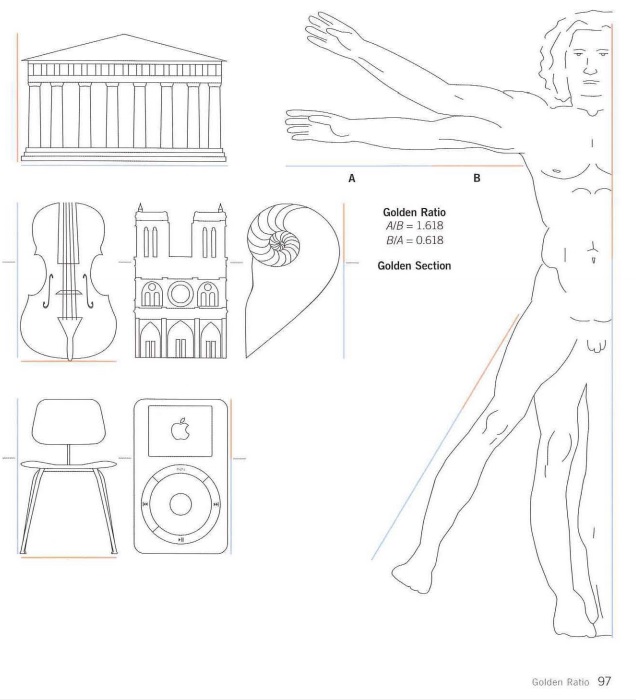

This preference for the natural extends to our next two terms, Golden Ratio and Fibonacci Sequence. The Golden Ratio is defined as the ratio between two segments such that the smaller segment is to the larger segment as the larger segment is to the sum of the two segments. This is larger segment is 0.618 compared to the sum of both equalling one. This is a little dense to type out and read, but can be understood much easier visually.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_ratio#/media/File:Golden_ratio_line.svg

Luckily, there are many depictions of this ratio being examined in relation to many beautiful man made and natural objects. Lidwell cites that, “the golden ratio is found throughout nature, art, and architecture.” Along with Mondrian and da Vinci paintings, pine cones, seashells, and the human body are used as examples of things that possess this Golden Ratio. In fact, it is the cover of the book itself.

These things are said to be subconsciously preferred, appreciated and found beautiful. Eventually, using this ratio became a conscious strategy, and part of a template for all kinds of works and designs. Lidwell suggests exploring golden ratios in design, “when other aspects of the design are not compromised”.

A similar phenomenon of intrinsic aesthetically value is the Fibonacci Sequence. A Fibonacci Sequence is a sequence of numbers in which each number is the sum of the two preceding numbers. An example being 1,1,2,3,5,8,13. Lidwell cites the “seminal work” on the Fibonacci Sequence, “Liber Abaci” from 1202. Saying, “ubiquity of the sequence in nature has led many to conclude that patterns based on the Fibonacci sequence are intrinsically aesthetic and, therefore, worthy of consideration in design”. Much like the Golden Ratio, the Fibonacci Sequence can be found in nature: the number of flower petals and bones in the human hand. Also similarly, after identifying this pattern, artists and designers started consciously using it in their work. The Golden Ratio and the Fibonacci Sequence are closely linked: the division of any two adjacent numbers in a Fibonacci Sequences yields an approximation of the golden ratio. Earlier on, it is less accurate, but as the sequence increases it becomes more so.

Themes, and my take

The grouping of these terms points to ideas about what is considered average, normal, natural, intrinsic, and perhaps some kind of concept of ‘perfection’. We want to be able to measure these things, thinking of Normal Distributions, which can be implemented in grading or formulation of public policy. We want to be able to model these things, thinking of a perfectly beautiful face. And we want to believe in a kind of mystical property for these things that we want. The subjectivity of beauty meets the objectivity of math with the Golden Ratio and the Fibonacci Sequence. Humans simply just prefer these things, and even though we don’t know why, there is a kind of mathematical code that points the way to replicating it.

To Lidwell’s credit, he qualifies and hedges all of these terms. He notes Normal Distribution is a statistical model by which to analyze measurements, not an inherent truth. This is in addition to reminding us that with design, we should actually pay more attention to the outliers, the 1% and 99% populations, in order to closer make a design that is effective for 100% of the population. This sentiment was echoed in the Objectified documentary with the designers trying to create gardening shears.

The Most Average Facial Appearance Effect is peppered with qualifiers, “the effect is likely the result…”, “…it is possible a preference for averageness…”, “If this is the case..” and so on. And the Fibonacci Sequence and Golden Ratio have outright warnings. Lidwell cites that while there have been some studies that purport to show that people aesthetically prefer things that have these traits, these studies have also been challenged. But it seems that hasn’t prevented them from being adopted and spread among our zeitgeist.

In fact, in researching these things, I discovered a kind of online subculture of people complaining about the Golden Ratio and Fibonacci Sequences in popular culture.

Words:

https://www.fastcodesign.com/3044877/the-golden-ratio-designs-biggest-myth

https://www.lhup.edu/~dsimanek/pseudo/fibonacc.htm

Images:

http://www.smash.com/celebrity-faces-become-hilarious-distortions-made-fit-fibonaccis-golden-ratio/

Part of this seems to be in reaction to a hyping up of both theories. “Fibonacci Numbers are found in nature,” seems to have been rounded up to, “THE NUMBER OF PETALS ON A FLOWER ARE ALWAYS FIBONACCI NUMBERS OMG!!!!” (when this is demonstrably not the case at all). This can be attributed to a misunderstanding of the theories and maybe some opportunistic hucksters looking to sell books and get advertising clicks, but the instinct to even amp up these concepts in the first place is very telling to me.

My take is that all of the terms I was given can be good general guides when looking for inspiration, searching for possible themes, and coming up with rudimentary methods of analysis. But there is a danger of feeling that they are inherent. And that danger is likely, because if pop culture around these concepts is any guide, we crave this objectivity and rock solid “normality”.

Using any statistical method of analysis, like Normal Distribution, can be dangerous if you aren’t paying attention to how you are collecting your data. Which can mess up your Most Average Facial Appearance Effect model of the “most attractive person,”: how many people did you analyze? From what places? Are they considered “familiar” or “unfamiliar” to your target audience? How would you know? And then if you have drawn your conclusions from less than ideal data, methodologies, and theories, this can keep you only focused on things that fit your conclusion. You only notice flowers that have Fibonacci petals, and don’t pay attention to the ones that don’t. Then after a long enough time, you wind up taking these theories for inherent facts. That is until you notice something that makes you question the whole thing…

http://lolworthy.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/trump-golden-ratio-fibonacci.jpg

Final verdict: Don’t throw the baby out with the bath water. But keep these concepts in context. Despite popular depictions, try to use these as design tools, not rules.