For our first Comm: Sound & Video class we were asked to read “The Ecstasy of Influence”, a Harper’s Magazine article by Jonathan Lethem, watch “Embrace the Remix”, a TED talk by Kirby Ferguson, and then do a soundwalk. I chose “Passing Stranger (East Village Poetry Walk)” by Pejk Malinovski.

I was so happy to see a common theme here: remix, sampling, appropriation, copyright, intellectual property, influence, the commons, art, originality. I’ve long thought about these topics. Some books that have influenced my ideas on this: Anarchist in the Library, by Siva Vaidhyanathan and Free Culture: The Nature and Future of Creativity, by Lawrence Lessig.

Being new to New York, I was happy to go on the East Village Poetry walk in order to get to know the neighborhood close to our school. But to also reacquaint myself with famous poets and writers that I am somewhat familiar with, and put them in their physical context within the new city I will now call home.

The audio tour was wonderful. Entirely immersive, while simultaneously making me hyper aware of everything around me. Usually great immersive art makes you lose track of the real world, but the audio tour put one of my feet in immediate reality and my other foot into a different world I was totally lost inside of.

I hadn’t thought much about walking tours before. But I greatly appreciate the form, now. I’ve already sent the link to a friend! This has made me on the look-out for other good ones.

I wound up doing the walk before watching the video and doing the reading, which I think was a good order. “Embracing the Remix” conjures up modern methods of artistic re-use: digital audio sampling in dance music, mashups, maybe some wild and bizarre video art. However, having just walked out of an auditory time machine, these concepts felt far more old, established, and anchored in the artistic landscape. How can we be scandalized by Danger Mouse’s Gray Album when William Burroughs was doing his cutup technique forty years earlier? How far away is sampling a James Brown drum break from the folk music tradition?

In my experience, these types of meditations are very useful when trying to expand people’s understanding of intellectual property. Infringement is usually cast as a new, digital interloper that is smashing the established order. I was delighted to see Jonathan Lethem bring up the concept of “The Commons” in his article, which is also heavily featured in the books Free Culture and The Anarchist in the Library. We’ve had structures of ambiguous ownerless-ness that serves society since the middle ages.

I love Lethem’s casting of language as a kind of commons. Never thought of it in that way before. However, I don’t think that this awesome feat of philosophical acrobatics is even required. Take the plain, original physical commons: a piece of land that the community’s farmers could all use to for their livestock to graze on. A piece of property used by all that is owned by none. It lies outside of what would normally be a capitalist (and at the time, feudal) structure of ownership.

From the lords to the peasants, the value was obvious. They didn’t need 21st century graduate philosophy courses or economic statistical models to understand it. It was a natural, intuitive way of casually organized sharing that benefited everyone in the town. These ideas aren’t solely the theories of lefty digital radicals with their MP3s and their hip hop. They are the completely plain deduction of an English farmer from one thousand years ago.

And once you’ve given people a kind of “meat and potatoes”, “salt of the earth” challenge of intellectual property and copyright, you can move on to the instances where it hides in plain sight in the present day: libraries. Again, we could go on to be high minded about this, but I like to make it plain. If you had never heard of a library before, you might think that creating one would bankrupt book stores. However, this didn’t happen. And even if we decide to give the devil his due, and perhaps admit that the existence of a library could represent a non-zero amount of money lost for book sellers… we simply do not care as a society. Whatever that cost is, we have decided that the value of the library (a kind of intellectual commons where the community can graze on knowledge) is simply greater than not having a library.

But these things are normalized to the modern citizen. We don’t view them as “new” things, but as institutions. They don’t seem challenging at all. But they aren’t “inherent”, they are decided upon by members of the community. This is why we see campaigns by vested interests to influence our opinions on such things, as Lethem points out in the “You wouldn’t steal a handbag!” MPAA anti-piracy commercials. The MPAA wants to make us feel that the digital equals the physical. That one MP3 downloaded illegally inherently equals one less song somewhere else in the world, and hence a lost sale, and theft.

I love reminding people that the digital isn’t physical, the concepts of “lost sale”, and so on. But I would also like to attack this target from the opposite direction. Namely, that our understanding and categorization of physical ownership is not itself set in stone or inherently fixed either.

In the introduction to Free Culture, Lawrence Lessig talks of the early days of flight in the United States. Building upon the knowledge of the Wright Brother’s innovation, a budding aviation industry spread its proverbial and literal wings. Up until this moment, US property law described ownership of land as not just the surface of the plot but also “an indefinite extent, upwards.” Lessig points out the obvious hurdles this put in front of newly flying aircraft: was a trip over someone’s farm considered trespassing?

This was tested in the Supreme Court when a farmer sued the US military for flying over his land. The noises from the aircraft scared his chickens, who would fly into the walls of their coop and kill themselves in panic. He was suing in part because the planes were trespassing, as ownership of his land extended above his property “indefinitely”.

I will condense the conclusions, but I encourage everyone to read Free Culture as it really is a great and accessible read for everyone. Essentially, the Supreme Court rules against the farmer and in one fell swoop redefines property rights fundamentally. No, you do not own the air above your property “indefinitely upwards” anymore. The reason? Entirely pragmatic. This new invention of air travel is simply too important to be held back by this definition. So for the sake of letting this innovation flourish and hence increase the common good, we will redefine what it means to own something physically. A wave of the hand and a commons of the air is created, simply because it is obviously a good thing.

We make these changes, bend these rules, and tolerate what might in some way be considered a transgression, because at the end of the day it is simply worth it. What is best for everyone? America gets a cultural value out of folk music, with its casually anarchist traditions of copying and ownership. On the East Village Poetry Walk, you could see the added benefit it gave: by allowing beat poets to continue on in that tradition and “steal” from folk, in its content and ethos.

And this is great, and many could be heartened by this cultural history lesson. But it doesn’t have to stop there. If we take an even broader and more practical view, folk is not just also the beat poets (and hip hop, and dance music, and Danger Mouse, and onward into the musical tradition). Because of our flexibility and pragmatism and desire for obvious common good, folk is a library. The beat poets are airplanes. And based on our readings, the remix is a new smartphone or maybe even the cure for cancer.

Love this stuff. Great first reads, views, listens and walks for this class. Very excited at where this all is pointing towards in terms of our work and conversations for the next class.

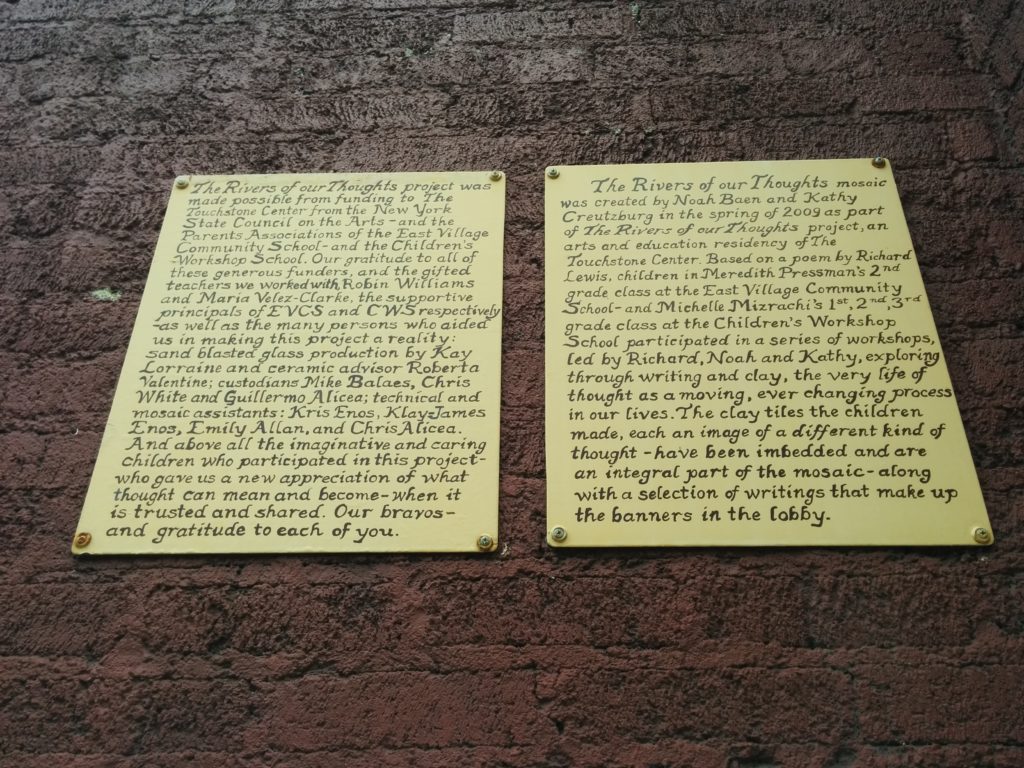

Some photos from the walk: